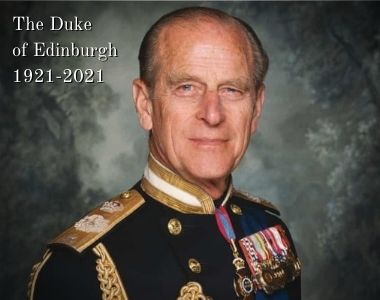

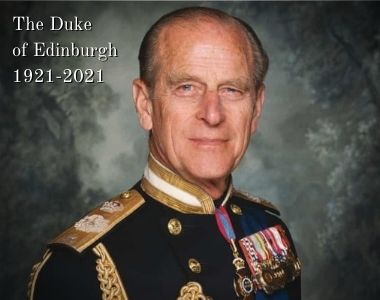

Prince Philip, The Duke of Edinburgh passed away aged 99 on Friday 9 April 2021. His was a life of extraordinary events and circumstances and of outstanding heroism during his time with his beloved Royal Navy. It wouldn’t be overstating the issue to say that the Senior Service was the moulding force that took a young refugee Greek Royal and tempered and shaped him into the remarkable man he would become.

Born on Corfu in 1921 to Prince Andrew of Greece and Princess Alice of Battenberg, the young Philip was born into the lower echelons of the Greek Royal family but the early 1920s were a troubled time for Greece and on 27 September 1922 the new Greek military Government swept into power and banished the Royal Family of King Constantine I. Within days the young Philip and his entire family were escaping the country with the youngster being bundled aboard the British warship CALYPSO in a cot fashioned from an old orange crate. He was just eighteen-months old and had become an exile but had been saved by the Royal Navy. It wasn’t the only early connection the future consort of Queen Elizabeth II would have with the Royal Navy as his maternal grandfather, Prince Louis of Battenberg, had been Admiral of the Fleet and First Sea Lord, although in 1914 he had to resign following the rise in anti-German feeling at the start of the First World War.

Philip and his family led a peripatetic lifestyle across Europe until they came to England where they put down roots. The young Philip was sent to Gordonstoun School and graduated just before Britain was, once again, facing war with Germany. As a minor Royal at the time Philip expressed a desire to serve the country by joining the Royal Air Force, but his uncle Louis ‘Dickie’ Mountbatten persuaded him otherwise. Mountbatten was in command of the destroyer KELLY at the time and convinced Philip that the senior service was a far better option for a Royal. So, he enlisted as a midshipman at Britannia Naval College in Dartmouth where he excelled winning the King’s Dirk, for the best all-round cadet of the term and then also taking the prize of best cadet in college during his year. Another prize he received was of a more personal nature, in July 1939 when King George VI and Queen Elizabeth visited the College with their daughters Margaret and Elizabeth it fell to the best cadet to escort the young princesses around the complex. He was clearly enamoured with 13-year-old Princess Elizabeth as the princess’s governess, Marion Crawford, later recalled, ‘he showed off a great deal’ and the feeling was mutual. When the Royal party sailed away in the Royal Yacht, the VICTORIA and ALBERT, they were escorted out the River Dart by cadets in rowing boats. When the other cadets had stopped rowing, Philip continued to row out into the English Channel, even when King George VI called him ‘a bloody fool’.

As a potential heir to the Greek throne, Philip was, initially, kept away from battle zones particularly as at the start of World War Two his home country was neutral, but Louis Mountbatten saw to it that by pulling some strings the outstanding young officer would see battle up close and personal. Philip’s first posting was to the battleship RAMILLIES that was at the time escorting Australian troop convoys in the Indian Ocean. He would later spend time aboard the cruisers KENT and SHROPSHIRE before returning to battleship life aboard the VALIANT.

When Greece entered the Second World War on the side of the Allies the decision was taken that Philip could serve in one of the most hotly contested warzones at the time, the Mediterranean. During the Battle of Matapan, on the night of March 28, 1941, Philip was in charge of one of the battleship’s searchlights. Radar was in its infancy at the time and during the night encounter with the Italian fleet it fell on the young prince’s shoulders to illuminate any targets. In the 2012 book, Dark Seas: The Battle of Cape Matapan, Prince Philip wrote the foreword: “I seem to remember that I reported that I had a target in sight and was ordered to ‘open shutter’. The beam lit up a stationary cruiser, but we were so close by then that the beam only lit up half the ship. At this point all hell broke loose. All our eight 15-inch guns started firing at the stationary cruiser, which disappeared in an explosion and a cloud of smoke. I was then ordered to ‘train left’ and lit up another Italian cruiser, which was given the same treatment.” The Italians did not, however, go down without a fight. The searchlight position where Philip stood was raked with gunfire and several of his fellow shipmates were cut down by the bullets, but Philip survived.

Three Italian cruisers and two destroyers were sunk at The Battle of Matapan with 2,000 sailors. For his actions Philip received the Greek War Cross for heroism. On his way home from the Mediterranean aboard the troopship RMS EMPRESS OF RUSSIA, Philip displayed his industriousness and willingness to get things done by entering the boiler room and shovelling coal into the ship’s boilers when the ship had no stokers. Philip toiled for so long that his hands were covered in blisters that made it hard for him to hold a fork during mealtimes. Such dedication was soon rewarded with a promotion and posting to the destroyer WALLACE of the Rosyth Escort Force on convoy duties in the North Sea.

It would be onboard the WALLACE in 1943 that the future Duke of Edinburgh would save his ship and his shipmates from a German bomber attack during the Allied invasion of Sicily covering a Canadian beach landing. Philip was the destroyer’s first lieutenant and second in command when Luftwaffe bombers targeted the ship during the night. The aircraft was getting ever closer with their bombs and fearing that the next attack might be the one that sinks the destroyer Philip came up with a brilliant plan on the spur of the moment. He lashed a wooden raft together on the deck and launched it into the water. At each end was a smoke float and from the air it resembled a heavily wounded warship and a better target than the WALLACE that sat some distance off with all lights dimmed. The plan worked when the German aircraft attacked the dummy raft.

As the war moved into the Pacific Philip joined the British Pacific Fleet and was appointed to the destroyer WHELP. During OPERATION MERIDIAN II in 1945 two airmen from an Avenger dive bomber crashed into the sea nearby the destroyer. The aircraft was sinking fast, and the airmen were struggling to escape. The Duke would later in life play down the significance of the event stating in a BBC Radio 4 documentary that: "It was routine. If you found somebody in the sea, you go and pick them up. End of story, so to speak." He was aboard WALLACE when he witnessed the Japanese surrender in Tokyo Bay on 2 September 1945. Two years later he married Princess Elizabeth and was posted to serve on the destroyer CHEQUERS based in Malta. For the Princess and the Duke, a carefree life awaited them as they welcomed Prince Charles on 14 November 1948 and Princess Anne on15 August 1950. As a promising naval Lieutenant Commander, he was given command of his first warship the sloop MAGPIE in the Mediterranean from 2 September 1950 and 1952. It would prove to be his only command as on 6 February 1952 his father-in-law, King George VI died, and his wife became Queen Elizabeth II. His role in the Royal Navy was deemed incompatible with that of being the Queen’s consort and he stepped away from his beloved Royal Navy for the love of a Queen and nation. "At that time, I had not thought that was going to be the end of a sort of naval career. And that sort of crept upon me. And it became more and more obvious that I could not go back to it. But it's no good regretting things. It simply didn't happen. And I've been doing other things instead.”

Several years after the end of World War II, Philip became Admiral of the Sea Cadet Corps, Colonel-in-Chief of the Army Cadet Force, and Air Commodore-in-Chief of the Air Training Corps. The following year, he was promoted to Admiral of the Fleet, Field Marshal, and Marshal of the Royal Air Force. On his 90th birthday the Queen made him Lord High Admiral of the United Kingdom, one of Britain's great offices, as a sign of respect and acknowledgement for what he had given up for her.

The Duke of Edinburgh’s sometimes acerbic wit got the better of him, but later in life he spoke about how the war had affected him. "It was part of the fortunes of war," he said. "We didn't have counsellors rushing around every time somebody let off a gun, you know asking 'Are you all right – are you sure you don't have a ghastly problem?' You just got on with it." Former First Sea Lord Sir Jonathan Band recalled the Duke of Edinburgh: "He was a servicemen at heart, he was good at it and he enjoyed it. There was no ego in the man. I think the Navy provided him with an anchor for life. He was always very proud in the uniform and his sense of duty and correctness dovetailed quite well when he married the princess.”

The Duke of Edinburgh was a Royal Navy man through and through. His entire life was dominated by the oceans. He said: “The environment is completely different to anything you'll find on land. You're at sea and exposed to the elements in a way you never are ashore. At sea you're in a cockleshell in this enormous expanse of the ocean. So that tends to cut you down in size a bit."